Blog

April 5, 2012 — Is Science Fiction Preparing Us For the Future? – Mineral Wells Index

– Mineral Wells Index

Remember Dick Tracy’s 2-Way Wrist Radio? What a great idea, and when the real thing came along we knew exactly what it was and we were ready for it. That hasn’t always been so. In the early twentieth century one of the grande dames of New York City was asked why she was the last person on Fifth Avenue not to have a telephone. Her answer was that she didn’t need one. When she wanted a servant she had only to pull the bell cord. The idea of personal long-distance communication was completely beyond her.

Arthur C. Clarke, one of the greats of science fiction, came up with the idea of geostationary satellites for communication back in 1945. He called them “extra-terrestrial relays.” The geostationary orbit around the earth, where most of the satellites are parked, is now referred to as the Clark Orbit in his honor.

Even in a work like Frankenstein, Mary Shelley prepared us for a future not of zombies or gollums but of perplexing ethical questions. In her novel, Dr. Frankenstein studied how the body broke down, chemically, after death and strove to reverse that process in order to bring dead organisms back to life—specifically, his “monster.” We still wrestle with questions of life, when does it begin and when does it end? She further raised questions as to the responsibility of the creator who artificially brings life into the world. That, as pointed out by science fiction writer Robert Sawyer, happened almost two hundred years ago, 41 years before Darwin’s “The Origin of Species” and 135 years before the discovery of the structure of DNA.

I’ll never forget the colossal misunderstanding I had about personal computers. I worked with computers as a graduate student at Princeton and even wrote a how-to book on the use of computers for the generation of sound. But this was back in the old days of the massive IBM 360s with tape drives that took up a whole room. Years later, when personal computers came out, I figured I didn’t need one. I could type practically as fast as the ball on my new IBM Selectric could move. Clearly, I didn’t understand the scope of the PC.

In 1932, Aldous Huxley gave us a heads-up on modified humans in his chilling novel “Brave New World.” In an article in “Astounding Science Fiction,” Cleve Cartmill speculated how a uranium-fission bomb might be made a year before Hiroshima. The FBI demanded that the magazine be recalled, but it was too late; the magazine was already out. In these extreme cases, specific ideas were proposed in advance of the actual events.

Arthur C. Clark said, “one of the biggest roles of science fiction is to prepare people to accept the future without pain and to encourage a flexibility of mind. Politicians should read science fiction, not westerns and detective stories. Two-thirds of 2001 is realistic – hardware and technology – to establish background for the metaphysical, philosophical, and religious meanings later.”

If you write and want to improve your craft, consider joining the Brazos

Writers Group that meets the fourth Tuesday of every month at the Boyce

Ditto Public Library. For more information, call the library or Gerald

Warfield at 940-327-8789. Gerald is an award-winning writer of fantasy and

science fiction. See his website at http://www.geraldwarfield.com.

.

.

.

.

March 4, 2012 — The Value of Critiquing — Mineral Wells Index

Editors like Maxwell Perkins worked with many famous authors. There are fewer editors today. We have to make do with critiquing.

Criticizing someone’s writing is called critiquing. That’s different from every-day criticism in that it’s not personal; you are not criticizing the author him/herself. Yet a lot of beginning writers don’t understand that. I’ve seen writers get hot under the collar when they receive criticism of their work. That kind of misunderstanding can derail a writer’s growth because being critiqued is part of learning to write.

Even well-established authors send their work out to trusted readers for

critiquing, not because these writers aren’t good enough to produce a novel

or short story on their own, but because it is impossible to see one’s own

work from the point of view of others. What is crystal clear to you, what

is understood, what is implied may simply never have made it onto the page.

The popular image of the writer pounding the keyboard, ripping the pages

from the typewriter, and shipping them off to the publisher is, in fact,

fiction itself except, perhaps, in the case of some pulp writers like L. Ron

Hubbard. Take Hemmingway, for instance. He may not have had critiquers,

but he had an editor who did the same thing. One of the most famous editors

of all times was Maxwell Perkins who brought authors like Fitzgerald (The

Great Gatsby), Wolf (Look Homeward, Angel), and Hemmingway to greater

success than they could have achieved on their own.

Critiquing is more than correcting spelling and catching comma splices. It

is also more than family and friends saying what you want to hear. A good

critique will address basic issues like the effectiveness of the story,

consistency, character and scene structure. It may even extend to the

development of the story itself.

These days, the majority of material published is with little or no

editorial oversight, and that makes the critiquing process even more

valuable. One way to get critiques is to join an online writers’ group.

The most famous is Criters Writers Workshop, at http://critters.org/. It is

primarily for writers of speculative fiction, but there are others for faith

writers (http://www.faithwriters.com/critique-circle.php), romance writers

and non-fiction.

The best way to get face-to-face help is to join a local writing group. For

writers starting out, this is absolutely the best way to go. Collect a

group of writers and read one another’s works beforehand. When you meet, be

honest, and when you are being critiqued keep in mind always that your

colleagues are talking about the effectiveness of your writing, not you.

Feb. 5, 2012 — The Other Kind of Rhyme — Mineral Wells Index

To rhyme or not to rhyme. That’s one of the big questions for beginning poets. In fact, some people don’t even recognize verse as poetry unless it rhymes. But why is rhyme so important?

Rhyme was only one of several techniques used by the ancients to help them remember their stories. As such, rhyme is as old as poetry itself. Keep in mind that epics weren’t written down; they were told around a campfire or in the great halls of kings or lords, usually to some kind of accompaniment. They were passed from generation to generation by what we now call oral tradition, a fancy way of saying that they were memorized. Young boys apprenticed early to commit to memory prodigious amounts of epic poetry.

So what were the other techniques used by bards and troubadours, like Blondel, minstrel to Richard the Lionheart? They used formulaic patterns for scenes, rhythm, meter, alliteration, and of course, rhyme. As someone who recites his own poetry by memory, I can tell you that all these tricks help you to remember a poem.

We all know what rhyme is, but what is alliteration? It’s when two adjacent words start with the same sound rather than end with the same sound as does rhyme. Usually, it works better with consonances as in “bouncing baby boy.” Today, the technique is used mostly in jingles or trade names, like the ad for jaguar, “Don’t dream it. Drive it.”

One of the most famous uses of alliteration is Beowolf, the earliest of the great English epics and known to many of us today by Ray Winstone’s portrayal in the movie directed by Robert Zemeckis. The original epic poem was written in Old English, the language of the Saxons, which was closer to German than to modern English. Old English naturally favored alliteration over rhyme because of its stress patterns. The famous first line of Beowolf, in English translation, goes like this: “Now Beowulf bode in the burg of the Scyldings.” The three words that start with “b” constitute the alliterations.

Poetry in English eventually favored rhyme over alliteration, in part because of changes in the language, but—and this is my theory—English was greatly enriched by thousands of words from the French, thanks to William the Conqueror. If you are looking for rhymes, it helps to have a language with lots of words in it.

Still, alliteration remains a useful tool for poetry. Poe is famous for his use of alliteration. The third part of his poem, “The Bells,” starts: “Hear the loud alarum bells– Brazen bells! What a tale of terror, now, their turbulency tells!”

There are three sets of alliterations in that passage, one that begins with “l,” one with “b,” and the final one with “t.” Can you hear them?

The message for poets today is that we have a variety of tools at our disposal. Don’t discard any of them. (Did you catch the alliteration?) Explore the use of rhyme, partial rhyme, meter, metaphor, simile, hyperbole and alliteration. All these techniques can contribute to the rich stew we call poetry.

If you write and want to improve your craft, consider joining the Brazos Writers Group that meets the fourth Tuesday of every month at the Boyce Ditto Public Library. For more information, call the library or Gerald Warfield at 940-327-8789. Gerald is an award-winning writer of fantasy and science fiction. See his website at http://www.geraldwarfield.com.

Jan. 9, 2012 — Where Do Your Ideas Come From? — Mineral Wells Index

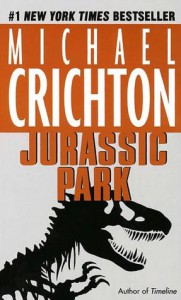

The idea behind a book can sell a lot of copies, like the idea behind Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park.

What if you could bring back dinosaurs by fertilizing reptile eggs with prehistoric DNA? Michael Crichton sold a lot of copies of Jurassic Park with that idea. Neil Gaiman, one of the superstars of speculative fiction, wondered if a baby could be raised in a graveyard by ghosts. Would it be possible? How would they change his diapers? Could they keep him hidden? The answers, in his novel, The Graveyard Book, keep you turning the pages.

Dynamite ideas are hard to come by, and it’s only natural to wonder where a writer gets them. That question is made fun of by a lot of writers, but I take it seriously. For myself, I get most of my ideas from media coverage of nature. I saw a National Geographic special on how bees pollinate some unusual orchids in South America. I was fascinated and wondered, what if people pollinated orchids like that? What would be their motivation? And I was off and running.

I saw a TV special about the deep-water vents in the Pacific and the strange life that clusters around these unusual thermal hotspots. It gave me the idea to write a short story about a frozen planet where life clustered around active volcanoes that poked up through the solid ice cover.

It’s important to realize that ideas are very limited. An idea is not a book, and it takes a lot of work, insight and technique to build a story around an idea. For instance, my story based on orchid pollination turned out to be about how disappointment in love can lead to maturity. The story based on deep-water vents turned out to be how persistence can eventually overcome small minds and prejudice.

One of the best ideas I’ve heard for generating new ideas, other than simply getting them from the media or nature, is to put two dissimilar things together. Any two things. What about a dragon egg and a boat? How could those two dissimilar things interrelate to form as story? Well, Naomi Novik did it in His Magesty’s Dragon. The egg hatched on the ship, and the crew was beside themselves trying to care for a baby dragon in the middle of the Atlantic.

So think of some of your own ideas. How about a story that relates a tombstone and a rusty nail? What about an apple and a snake? Woops, that one’s already been done. However you get your ideas, be warned. The idea is just the beginning. There’s a lot of work ahead before you have a story.

If you write and want to improve your craft, consider joining the Brazos Writers Group that meets the fourth Tuesday of every month at the Boyce Ditto Public Library. For more information, call the library or Gerald Warfield at 940-327-8789. Gerald is an award-winning writer of fantasy and science fiction. See his website at http://www.geraldwarfield.com.

Nov, 28, 2011 — Finding the Inspiration to Write — Mineral Wells Index

Writers need inspiration. Inspiration is not the same thing as a good idea. Inspiration is more like a frame of mind where it’s possible to come up with good ideas—and then having the motivation to follow through on them.

Jack London, the great American writer of the early twentieth century, said “You can’t wait for inspiration. You have to go after it with a club.” What he meant was that you have to actively put yourself in a situation where inspiration is possible. In fact, inspiration is a by-product of that situation, be it within nature, contemplation, a dream, whatever.

The out-of-doors brings inspiration to many. Chris Hunnewell, a new member of the Brazos Writers’ Group, says “I take a walk around my neighborhood, making sure to swing my arms. Usually by the time I get back I’m recharged to jump the hump.”

The author finds inspiration at the duck pond in Woodland Park Cemetery. On this particular day, kids were fishing, and they became the subject for his poem.

I, too, find that nature helps. The duck pond in Woodland Park Cemetery is one of my favorite places. The flat, placid water in contrast to the trees yields a kind of perspective that is conducive to writing. But last time I went, I found four boys fishing. Their presence was so distracting that I thought I couldn’t write until I realized that my poem was to be about them. Nature’s inspiration can have the added bonus of surprise.

Others can find inspiration in mundane activities. Lauri Mays, another member of the Brazos Writers Group, says “Ideas come to me when I’m engaged in a mindless activity or on auto pilot… Driving, vacuuming, or running water while I’m washing dishes sends my mind chasing after my characters.”

Troy Stone, a local writer who writes a poem a day (that’s a lot of poems), takes the broad view. “Inspiration comes from reflection on a day’s happenings, events, even dreams.” For him, it is quiet time that elicits the desire to write.

So what’s the answer on getting inspiration? James Chartrand, who blogs extensively about writing, says “Achieving inspiration means forgetting about it completely. Instead of seeking it out, we need to disconnect from the quest… Take a break. Go for a walk. Read a book. Play music. Give your brain something else to do… Let inspiration sneak up on its own until it leaps out in a sudden burst of idea.”

I agree. Inspiration, just like happiness, is the byproduct of something else. It’s peculiarly resistant to a frontal attack but loves to catch you unaware.

October 30, 2011 — Let’s eat grandma! – Mineral Wells Index

Oh my, and she is such a nice old lady, too. But wait, perhaps we can save her! Yes, a comma right after “eat” should do the trick. “Let’s eat, grandma.” Much better.

The need for punctuation is not always so urgent, but from its inception, the purpose of punctuation was clarity. The earliest writing systems, hieroglyphics and cuneiform did not use punctuation. It was probably the Phoenicians who invented it, along with the alphabet.

The first example of punctuation we have is on a stone tablet commemorating the victory of the Moabites over the Israelites carved in 840 BC. It was written using the Phoenician alphabet and employed horizontal strokes to indicate the grouping of words. Later, the ancient Greeks used dots for punctuation, a dot on the base line, a dot mid-way up, and a raised dot roughly equivalent to the colon, comma and period.

Now, here’s the rub. Scholars have claimed that these early markings were used by Greek playwrights, such as Euripides and Aristophanes, to tell the actors when to pause, and that punctuation today is for the same purpose. You pause at a comma or period.

But it ain’t so. You might pause at a comma, but you might not. Punctuation is to indicate the structure. It divides strings of words into sentences, clauses and phrases. In every writer’s group I’ve ever been in, people have said that a comma meant a pause. It doesn’t work. Try reading a passage strictly pausing at the commas. You’ll find that you run right over some. And it doesn’t matter. As long as the reader understands the structure, i.e., what’s being said, the meaning can be projected, pause or not.

In the example advocating cannibalism, the comma before “grandma” is there not to indicate a pause, although you do pause there, but to signal that we are dealing with direct address. Someone is being spoken to, namely grandma. We understand that meaning, and we can project it when we speak.

So long as the actor knows the meaning of the sentences and can project it, the punctuation can be ignored. In fact, one of the first things famous acting teachers, Stella Adler, told her students was to ignore the punctuation.

As fewer people read, one finds the strictures of punctuation increasingly ignored. People seem to think that if they just punctuate like they talk, that’s all that’s necessary.

I’ll end with another famous example. There’s a book with the title “Eats, shoots and leaves.” This, presumably, was the sentence describing a panda at a metropolitan zoo. The comma, in this case a “series” comma, indicates that these actions do occur in a series: the individual eats, then shoots (presumably a gun), and then leaves. Without the comma, “eats” and “shoots” become objects of the verb “eats,” and the phrase makes sense as a description of a panda. Lynne Truss uses this example for the title of her excellent book. The Truss book, unfortunately, has some British usage. A better book for brushing up on your American English and punctuation is “Painless Grammar,” by Rebecca Elliott.. .

.

September 18, 2011 — More Local Authors Publish Their Own Books — Mineral Wells Index

There are many reasons why someone would want to publish a book. The two authors we’ll discuss this time both have a message, and for both, self-publishing was the way to go. Thomas F. Kennedy’s book is a philosophical approach to life. “Self-help” for others, he modestly styles his book. Lauri Mays wrote her book as a compilation of brief vignettes from her life all of which illustrate, in some way, God in everyday life.

Like one of our authors last time, Lauri Mays published her book, “God in the Cat Box,” through CreateSpace (https://www.createspace.com/Products/Book/). Unlike Cuyler Creech, however, she elected to have CreateSpace format her entire book. A number of different production venues were offered, and she chose a package costing $1,200 which included complete page production, art and cover. She only had to supply CreateSpace with her book in a WORD file along with ten photos. She also paid extra for editing. The editor then worked on her manuscript and returned it to her electronically with “red-line corrections.” That is, his suggestions were indicated in red, and her job was to go through the manuscript and accept or reject, electronically, each one. Lauri wasn’t familiar with red-line corrections, and she called the publisher who walked her through the process. Turns out, it’s a standard feature of WORD although few people know how to use it.

The editing covered spelling and punctuation and other suggestions like writing out abbreviations which were commonplace to her but which others might not understand, like DPS for Department of Public Safety. Sometimes, she disagreed with the editor. For instance, he took out most of her exclamation points, saying that over-use of exclamation points was not professional looking. While she was free to reject those changes, Lauri went along with them. “If you are paying for advice, you might as well take it,” she said. She has just finished the editorial process, and is pleased with the result.

Her book will be about 100 pages, and there is no publication date, yet. “They are still working on the cover,” she said, and she can reject any cover she doesn’t like. “The entire process takes a minimum of ten weeks, longer if the manuscript is sent back and forth and if covers are rejected.”

Lauri also has the option of pricing her own book which will be listed in Amazon and available in hard copy and electronic formats. Amazon adds their own charge to her base price, but she believes the cost will be about $15.95. Her advice to authors who want to publish their own books? “If you’re happy with your own editing and formatting, you can publish your book cheaper by going with PublishAmerica (http://www.publishamerica.com/), but only if you know what you are doing.”

PublishAmerica was discussed in the previous article in this series. They take the rights to the book and set the price. They have been criticized for publishing indiscriminately anything sent to them. Wikipedia reports that one author, in a sting operation, sent them a 300 page manuscript which consisted of the same 30 pages ten times—and PublishAmerica agreed to publish it.

Artist and writer, Thomas F. Kennedy opted to go with a different self-publisher, Lulu (http://www.lulu.com/). The title of his book is “The 1st And Last Truth.” It espouses a philosophical approach to life, independent of religious dogma. You can see more about his book and its message on his lulu page at: http://stores.lulu.com/1tomkennedy.

Tom is an accomplished artist and provided the art and page layout of his book, uploading it directly to Lulu in “pdf” format. He was able to set the price, and Lulu made the book available in hard cover ($28.88) and in electronic format ($7.49).

He was happy with the result. When asked about advice to someone self-publishing he said, “it’s all about distribution.” Having mastered the problems of putting the book together, that was his main concern. “There is a monopoly on it,” he warned.

But Tom did something else in the course of publishing his book different from any of our other authors. He dictated the initial draft to a computer. He made use of a speech recognition software called Dragon Speaks (now Dragon Speaking Naturally). In the version he used it took three months for him to calibrate the software to his speech patterns and nuances. He then dictated the book, and the software rendered the speech into type which appeared on his computer screen, including punctuation. Of course, he had to edit the initial copy, but use of this device greatly reduced the burden of inputting the manuscript, ideal for someone not proficient at keyboarding. The current version of Dragon, home edition is $99.00 available at http://nuance.com/for-individuals/by-product/dragon-for-pc/index.htm.

If you are a writer and would like to improve your skills, consider joining the Brazos Writers Group that meets the fourth Tuesday of every month at the Boyce Ditto Public Library. For more information, call the library or Gerald Warfield at (940)327-8789.

.

September 4, 2011 — Local Authors Publish Their Books With Different Results – Mineral Wells Index

People are publishing their own books these days. Perhaps you’ve considered publishing yours? But just how involved is it? What does it cost? Do you get any royalties, and most important, how do you get listed on Amazon?

The good news is that if you do everything yourself, it can cost practically nothing to publish your book. But before we get into details, we need to consider what publication means. In the old days, an author submitted his or her manuscript to publishers, either directly or through an agent. If the author was lucky, a publisher wanted to publish his or her book. This usually involved paying the author an advance, editing the manuscript, printing and distributing the book, promoting the book, and finally paying the author royalties on the sales of the book.

Nothing is the same in self-publishing. You can pay a publisher to print multiple copies of your book and hold them in inventory or have them shipped to you. This is the most expensive way since you have to pay for all those copies. Or you can have a publisher make electronic copies of your book available in one of several formats like Kindle or Nook, in which case there is no inventory to pay for. Most self-publishers offer a combination of these approaches by making the book available both in hard copy and through electronic media. The hard copies, however, will be printed only on demand—when someone orders one. Bottom line, you don’t have to pay for printing an inventory in advance. I checked with four local authors who have recently published their own books to see how they did it.

Local teenager, Cuyler Seth Creech, gave a reading at the Boyce Ditto Library last week from his first novel, Shifter. Copies of Cuyler’s young adult book, a handsome 342-page paperback, was available for purchase. Cuyler created the pages and the cover himself, so all he needed a publisher to do was produce hard copies of the book, generate an electronic version, and make both available to the public for sale, in short, he needed distribution.

He went to CreateSpace (https://www.createspace.com/), a flexible company that produces books, CDs and DVDs. Among the services CreateSpace offers is cover art, editing, and marketing. Cuyler wanted none of these services (which cost) and simply delivered his book pages to them ready to be digitized. There was no up-front cost to him and no minimum number of books he had to buy. Create Space told him what their cost would be per book, and Cuyler was then free to set the price himself. Whatever he charged above cost, went into his own pocket. Create Space did no advertising, but they listed both hard and electronic versions of the book on Amazon (this is the all-important distribution), and now they provide Cuyler with a periodic accounting of how many books he’s sold and pay him everything they receive above cost.

In his case, the process was deceptively simple. Cuyler did not submit a mere typescript. He created the cover himself. He laid out the pages in the proper font, inserted the headings, page numbers and chapter breaks himself. CreateSpace simply reproduced what he gave them. The down side of that process was that he had no editor. No one corrected the mistakes in his manuscript. He also had no promotion or advertising. Unless he takes out ads, goes on speaking/signing tours, or blogs like mad, the only thing that will sell his book is word of mouth. On the up side, he retained the rights to his book. He set the price, and he is under no obligations: he can sell one book or a million. It’s listed in Amazon, and it cost him practically nothing.

Another local author, Linda Jensen (penname, S.L. Jensen) did not have such a good experience. She published her mystery novel, The Bridge Collapse Murder, with PublishAmerica in Baltimore. PublishAmerica calls itself a publisher, and they do take the rights to the book (like a traditional publisher), so Linda expected traditional publishing services from them. PublishAmerica produced her 185-page book with no up-front cost. However, they decided on the price of the book themselves, setting it so that she would receive an 8% to 12% royalty. She had no say in the cover. She expected some editing, but she received none. In fact, the transition process introduced new errors, not in her original manuscript. They also locked her into a contract whereby they controlled the rights to her novel for seven years. She received no marketing and found the staff hostile when she tried to speak to them about these issues. The end result was that she eventually got the rights to her book back and the considerable inventory of her books already printed. Now, however, she doesn’t have a publisher to manage distribution, and as a result, she finds that Amazon currently lists her book at $90.21 for a new copy although only $16.00 for a used copy. Recently, in a press release, she said, “Used copies might be available in a few places but basically this book no longer exists. The ISBN assigned to the book is also no longer valid.”

If you decide you don’t want to go through the hassle of submitting your book to traditional publishers or agents, or perhaps if your book isn’t really commercial (like a book of poetry or a family history), then self-publishing may be for you. The publishers that specialize in this are called “Indie” publishers. Here are the basics: you can usually publish your book with little or no up-front cost providing you do the editing, art, and layout yourself. You, of course, have the option of paying to have someone do those things for you, which is highly recommended, if you can’t do it yourself. You will not get an advance, but you will get royalties if your book is priced above cost. The package should include distribution, that is, listing in Amazon and other major book dealers. Linda Jensen’s advice is to check out an Indie publisher carefully. If you can, talk to authors who have already published with them.

Both the novels discussed are available in Mineral Wells at the Booksatchell. Next time, we will consider two other local authors who have self-published very different books.

If you write and want to improve your craft, consider joining the Brazos Writers Group that meets the fourth Tuesday of every month. For more information, call the library or Gerald Warfield at 940-327-8789.

July 10, 2011 — On the Death of a Writer — Mineral Wells Index

Royce Purefoy and the Brazos Writers Group were practically synonymous. He founded the group in the late 80s, and it was one of the first to use the meeting room at the library’s new location on a regular basis. When I lived in New York, I visited Mineral Wells once or twice a year and always went to the meetings. Several successful writers attended like poet Dorothy Lee Hanson, novelist Betty Brooks, and nature writer Don Price, among others.

Royce Purefoy and the Brazos Writers Group were practically synonymous. He founded the group in the late 80s, and it was one of the first to use the meeting room at the library’s new location on a regular basis. When I lived in New York, I visited Mineral Wells once or twice a year and always went to the meetings. Several successful writers attended like poet Dorothy Lee Hanson, novelist Betty Brooks, and nature writer Don Price, among others.

The group met every week. That’s hard to imagine now, with the pace of life ever accelerating. After the meetings we always went to one of the two (then) pizza places in Mineral Wells where conversation was lively. Royce often provoked exchanges between us by asking leading questions. He was one of the few people I have known who could discuss controversial subjects like religion and politics and remain completely objective without preaching or becoming emotional.

Early in his life, Royce wrote for newspapers. He was co-publisher and editor of the Mineral Wells Reporter and later wrote for the Mineral Wells Index. He must have published hundreds of articles, maybe thousands. In his fiction, none of which is published, he usually wrote with some kind of challenge. For instance, the novel he was working on at the time of his death was entitled “Stopping the World,” and he was writing it entirely in dialogue, no description, whatsoever, except what happened to be spoken aloud by the characters. That was a severe handicap, not to be able to set a scene or describe a person.

Royce was an extraordinarily quite man, very private, and he never promoted his own work that I know of. These days, writers are encouraged to network at conferences, concoct elevator pitches, brand themselves, and establish platforms of support by means of the Internet. Royce did none of that, for better or for worse.

In the writers’ group, his critiques were invaluable. For anyone bringing their story or poem to the meetings, getting it past Royce was a goal. No detail was too insignificant or to broad to escape his attention. He will be missed.

July 3, 2011 — Poetry and why kids write it — Mineral Wells Index

Marisela Hernandes reads a poem in Spanish by Pablo Neruda at the library's poetry bash during National Poetry Month

One would think, with reading and literacy on the decline, that poetry would fade away into complete obscurity, but the immense popularity of music, especially with young people, has given a new energy to the medium. Country western singers and rappers, in particular, routinely employ the standard literary techniques of poetry like double entendre, alliteration, simile and metaphor. As a result, even stand-alone poetry is enjoying a resurgence.

In April, former Texas Poet Laureate, Larry D. Thomas was in residence at the Texas Mountain Trails Writers’ Retreat in Alpine, Texas. I asked him why poetry was so popular with kids, and he said that the crucial factor was the intensity and immediacy with which emotions could be expressed. Kids have always responded to that.

I agree. The historical union of poetry, music, and youth can hardly be overestimated. In ancient times, great works of literature like the Odyssey, Beowulf, even the Epic of Gilgamesh, were all chanted by bards if not outright sung with musical accompaniment. And, like today, those early bards, the singers of their day, were trained at a very early age.

To celebrate national poetry month in April, the Boyce Ditto Public Library held a poetry reading attended by mostly high school students. They gave dramatic readings of their own and published poetry in English and in Spanish. Open mike night at the library has also brought out a variety of singers and poets. If you’d like to show off some of your poetry at the next open mic night “friend” Boyce Ditto Public Library on facebook for the dates. If you write poetry and would like to improve your craft, consider joining the Brazos Writers Group that meets every fourth Tuesday at 5:30 at the Boyce Ditto Library. For more information, call Royce Purefoy at 325-4174.

April 24, 2011 — “Wht r u doing?” — Mineral Wells Index

Many of us see texting as the latest assault on literacy. The average teenager, who can’t write in cursive, sends eighty text messages a day. EIGHTY! That’s according to the NY Times. I thought it might be different in rural Texas, so I checked with local teens. Some said it was more. None said it was less.

Perhaps it’s a positive sign that kids are writing more these days than they ever did in the past. But even so, is this kind of communication literate? What’s happened to spelling? Where are the standards?

While it may seem, initially, that texting is arbitrary gibberish, standards are creeping in. While writing this article I googled the ubiquitous phrase in teenage texting: “Wt r u doing?” and Google corrected me. It seems the proper spelling is “Wht r u doing?” However, on consulting with one of my nephews I was informed that “Wat r u doing” is also correct.

As much as we might perceive texting as a threat to literacy, the situation is much worse in some other countries. In China, for example, people are forgetting how to draw the traditional Chinese characters. The Education Ministry in 2008 said that teachers were complaining about dropping level s of literacy due to texting and keyboarding. The LA Times reports that it is common for people, even literate people, to forget how to render Chinese script after prolonged keyboarding. There is even a nickname for it, “tibiwangzi” meaning “take up pen but forget character.”

Many factors have come together to bring about the incredible rise in texting. For teens, texting is an immediate and handy means of coping with loneliness and alienation. They can easily reach out and stay in touch with their own select group of friends. It reminds me of Orwell’s Brave New World where children were raised in crèches that took the place of families.

Even non-texting adults are adopting some of the texting conventions. I see LOL (laugh out loud) and IMHO all the time. It’s also interesting that some of these transformations are distinctly adult. For instance, two teens I asked didn’t know what IMHO meant. It’s “in my humble opinion,” a phrase I don’t think you start using until you pass thirty.

My own view is that texting is a type of dialect, and there’s nothing wrong with dialect it you know when to use it and when not to. Texting is a complicated subject, and I’ll revisit it in future articles.

March 20, 2011 — “Have you ate yet?” — Mineral Wells Index

I hear the above phrase all the time. It makes me wonder if verb forms have gone the way of handwriting in public schools: eat, ate, eaten; see, saw, seen. It’s hard sometimes to tell if we are sinking deeper into illiteracy or if the language is simply changing.

One of the reasons a language changes is an influx of foreigners. When my ancestor, Pagan de Warfield, came to England in 1066, he brought William the Conqueror with him (ahem, or maybe it was the other way around). For more than three hundred years the royal family of England spoke French. England’s beloved Richard the Lionheart (the king that Robin Hood fought for) didn’t speak a word of English. So as a result of the battle of Hastings, 80,000 French words found their way into the English language (like beef, chapel and garage).

Another reason a language changes is regional dialect. Over a beer at Woody’s, I wouldn’t be surprised to hear “I ain’t goin’ to heaven.” But on Sunday morning at the First Baptist Church I would expect our recalcitrant alcoholic to say “I’m not going to heaven.” In other words, there’s nothing wrong with dialect if you know when (and when not) to use it.

Some people state, categorically, that dialect is wrong. Thomas Hardy (who wrote Return of the Native) said about dialects that they were “terrible marks of the beast to the truly genteel.” Today, we take a more liberal view and understand that dialect is a useful tool and can signal all kinds of things. Would Steven King have one of his characters say “Have you ate yet?” Of course he would, and with that construction he would be telling us something about that particular character.

Sometimes even the experts disagree. Take “prove.” I’m told that the 2009 SAT study guide states that the three forms are prove, proved, proved so that Miss Marple ought to say “The facts of the case have been proved” and not “The facts of the case have been proven.” It ain’t so. Every dictionary I’ve consulted shows that there are two forms for the past participle: both “proved” and “proven” are correct. (And “ain’t,” in this paragraph, shows the use of dialect for emphasis!)

However, there is no doubt (yet) of the correct form of my initial example; it’s “Have you eaten, yet?” Remember that the perfect tenses (the “have” forms) always use the past perfect of the verb, the third of the three forms I mentioned before, as in eat, ate, eaten. Of course, if the forms of the verbs are not taught or learned in school, then all bets are off. People speak what they hear, and more dialects are born.

March 6, 2011 — The Passing of a Bibliophile — Mineral Wells Index

From my series of articles in the Index

Mineral Wells lost a wonderful person in February, Clyde Bullion, age 79. Educated, gregarious, he was also a bibliophile, a lover of books. One of the ways you can tell a bibliophile is that when you look on their bookshelves you find that the books are lined up two deep. Of course, books piled up around their easy chair also help.

Clyde’s library was eclectic. He had rare books, like a signed copy of Amelia Earhart’s autobiography and a first edition of one of the OZ books. He even owned books he didn’t like. His comprehensive collection on World War II included an early German edition of Mein Kampf, by Adolph Hitler. It’s interesting, collecting books of which you don’t approve. Lord Chesterfield said that reading only books you liked was a sure sign in an uneducated person, and Clyde was certainly educated. He had a Ph.D. He was actually, “Dr.” Bullion.

In 1982 his books numbered 10,000. His forbearing wife, Jane, hasn’t inventoried the collection recently, but it spreads into four rooms of their house.

The Friends of the Library, of which he was a member, is collecting donations for books to be given in Clyde’s memory. You may drop your donation off at the Boyce Ditto Public Library, or mail a check. Be sure to make it out to “Friends of the Library” and mark it in memory of Clyde Bullion. For information, call the library at 328-7880.

A reader of my last column chastised me for having an electronic copy of “To Kill a Mockingbird.” She reminded me that the electronic rights to “Mockingbird” have not been released by Harper Lee. The reader was right! I deleted my copy.

Also, apropos my last article, the price of electronic readers continues to drop. Kevin Kelly an e-commentator, even speculates that Kindles will be free by the end of this year. The gimmick? They want you to buy the e-books.

March 1, 2011 — E-Publishing: The Editorial Burden

This whole epublishing thing has got me flummoxed. By pursuing agents and sticking with traditional submissions are we missing out on the ground floor of the next generation of publishing?

It seems to me that the huge marketing and distribution possibilities of epublishing are parallel, to a degree, with the heady days of pulp magazines. Without a doubt, pulps were the single largest sales outlet for short stories of their time. I can imagine young writers back then having conversations something like ours, whether to join the pulps or stick to more traditional and respectable venues.

The up side would have been that the pulps paid (sometimes in advance) and they had distribution. The down side was the lowering of quality. To my mind (and some of you may disagree) pulps issued in a drastic decline in the quality of what was being published. Stories appeared that would never have been accepted in traditional formats, and editing was poor and, in some cases, non-existent. I believe that speculative fiction still suffers from association with the pulps.

It’s easy to see the internet awash in publications when anyone can publish anything. I don’t mean to be elitist, but everything sent to a publisher is not necessarily worth being published–and certainly not without critiquing and editing. Imagine, for a moment, that all publishers decided tomorrow to open up their slush piles and publish everything in them–and to do so with no editing. How different would that be that from the current situation in epublishing? A book would only lack the imprimatur of a “respectable” house.

As someone pointed out, agents serve as gate-keepers. And one of the jobs of a good publisher is to enforce standards as to narrative, grammar and spelling, i.e., editing. Seems to me, that if you are going to self-publish, one of the most important things to do is resist the urge to get your work out there immediately. Instead, get it critiqued, and then get it edited, and don’t try to edit it yourself.

Shifting the editorial burden onto the author is one of the significant developments in epublishing. Perhaps a way of signaling to potential readers that you have been careful in publishing your work would be to publish your editor’s name along with your own. Why not start epublishing novels and short stories with the editors name right there along with the author’s?

Another possibility would be to have a certification statement. If I were choosing between a number of e-novels, one that bore a statement or logo that said “This work has been critiqued by Odyssey and edited by X” would get my attention. It wouldn’t be such a big step to have some kind of “Odyssey Certification” signifying quality, like an imprint.

Feb 21, 2011 — Exhortation to Brevity

At ConDFW last weekend, the panel on short stories chanted in unison the same old cant “tighten, tighten, tighten, cut, cut, cut.” But if, in your writing, you “feel wind from other planets” (to quote Stefan George), then description is vital. My take on this is that wasted words in any context are a crime, and in short stories the offense is especially egregious. However, context matters as does the vision of the writer.

While we are frequently reminded of what readers or editors want, such as brevity, there is another voice to which we must also listen. Without the vision of authors who have the courage to impose their own unique stamp on their writing, literature would simply be a pale ghost trailing after the appetites of the public. Don’t deny your own voice out of a desire to pander to current fashion or editorial bias.

It would be easy to say that good writing has no unnecessary description, but such general dicta seldom stand up to scrutiny. One wonders, for example, about the definition of “good” and “unnecessary.” That having been said, however, the exhortation to brevity is a good one. Developing writers usually insert description rather than develop it from plot or character. A sharp eye for what can be cut is essential.

Feb 6, 2011 – The Brazos Writers’ Group — Mineral Wells Index

I have begun an occasional series of articles in the Mineral Wells Index on writing. This is the first installment. It appeared in the Feb 6 Sunday edition and addresses people who might want to be writers but haven’t done much about it, yet.

- - - - - - -

So, how do you become a writer? After the basics of grammar and spelling you just write, right? Actually, there are a few more steps, and one of the most important is critiquing. That’s a fancy word for criticizing and being criticized. It’s a step many aspiring writers never take.

The Brazos Writers’ Group meets monthly at the Boyce Ditto Library for critiquing. Members post their stories or poems to a Yahoo web site, and everyone reads the works and writes their critiques before the meeting.

This might be a surprise for those who just want to read their story or their poem to a captive audience. In fact, a good critique group is more like a gauntlet than a ready-made audience.

First off, it’s a lot of work. You might have to read stories that you wouldn’t ordinarily read. But coming to grips with the shortcomings of another writer’s works sharpens your own writing. Then comes your turn to hear what the other writers think of your work. The point is, you learn from both these processes, from critiquing and from being critiqued.

Sometimes new writers are not prepared to hear criticism. Criticizing, or worse, being criticized seems downright rude. It can be a grueling experience, but it’s not personal. That’s imperative to understand in order to realize the potential of a writers’ group.

And what do you get for running this gauntlet? You get an objective view of your own work that’s practically impossible to get any other way short of setting your work aside and reading it a year later. You’ll find out whether your character development is effective or if the chain of events in your story makes sense. You’ll have your grammatical mistakes pointed out, not to mention those little pesky homophones that spellcheck doesn’t catch. But most important—and this is what it’s all about—you become a better writer.

If you think you might be ready to suffer the slings and arrows of your fellow writers (to quote from Hamlet), then the Brazos Writers’ Group might be for you. It’s made up of friendly and sincere folks. They meet on the fourth Tuesday of every month. More information? Call our group leader, Royce Purefoy, at 325-4174.

Gerald Warfield

Jan 1, 2011 — On Owning Ghosts (Feb, 16, 2011 – Mineral Wells Index)

I‘ve had a Kindle for about a year. I only use it for getting stuff immediately when I don’t have time to order it via snail mail or find it in a book store. The only thing I like about it is that I can enlarge the type.

I don’t really feel like I “have anything” when I buy an ebook. I hate the cover art in grayscale, and I doubt the artists are happy about that, either.

I subscribed to an emagazine, but the tiny screen is not really good for magazines.

At the Odyssey Writers’ Workshop this summer I’d like to have had Elizabeth Hand sign my copy of “Illyria,” but I’d read in on a Kindle. Too bad.

I hate not being able to get around in a book conveniently. I wanted to discuss “To Kill a Mockingbird” with my great niece (she’s reading it in school) but trying to find specific passages on my Kindle was impossibly slow. That’s a serious problem. I can’t hold the book in my hands and show somebody a passage. Yes, there’s the search function, but it’s slow and it brings up all kinds of passages you don’t want. If you don’t know the exact wording, or if the words you enter don’t happen to be particularly unique, the search will take all day. Nothing beats the random access of flipping real pages.

And ebooks are NOT cheap. I had thought that would at least be one virtue of an electronic reader, but you can get “used” copies of books (which are often brand new) and discount copies on Amazon cheaper than the electronic versions.

I don’t like having this little gray talisman that I have to go through to get access to my elibrary. If I lose it; if I break it; if I forget the charger, my elibrary virtually vanishes. A few months after I got my Kindle, the charging port malfunctioned. Suddenly, I had no electronic library. And what about the future? Is that reader going to last ten years? I doubt it.

And what if Amazon doesn’t exist in ten years? An elibrary really is bound to a provider. When Amazon goes, your library goes. Even it they just decide no longer to support their controversial DRM format (digital rights management) your library could be in danger of winking out. And what if they decide to start charging a maintenance fee? You’d have to pay or abandon your library.

It’s true that the Kindle/Amazon elibrary is not bound to that device. I can download an app (application) giving me access my ebooks on my cell phone, but, frankly, I don’t look forward to charging my phone any more frequently than I already do, and we needn’t even mention the size of the screen. Accessing ebooks via my PC is is a more attractive option, but if I wanted to do that, why did I have to buy that expensive gray talisman in the first place?

And I don’t like the control that Kindle has over what’s in my library. When someone powerful enough decides that they don’t want you to have a book, ZAP, they can remove it. Censorship of ebooks is waaaaaaaaay to easy. I have no doubt that politicians will eventually exploit spot alterations in ebooks when they want to change an image, color a fact, distort the truth.

One more thing, and this is hard to explain, I like being with books. I bought George R.R. Martin’s “Clash of Kings” recently. I don’t have anywhere near the time to start that Chihuahua killer (if the book is big enough to kill a Chihuahua when dropped from chest level…), but I love being reminded that I have it. I like seeing it in my house on the table at the foot of my bed. The ebooks that I have bought are not so tangible. I won’t see them in my house unless I conjure them with the gray talisman. I won’t be reminded of them by a chance encounter, looking for something else. It seems to me that my ebooks hover at the edges of my “real” library like ghosts who want to come in from the cold nether-world which they haunt. Sometimes I bring one in. That book I mentioned, “Illyria,” by Elizabeth Hand. I bought a real copy.

Gerald Warfield, Jan. 1, 2011

P.S. Oh, dear. It occurs to me I should apologize if I’ve offended anybody. Every once in a while I can’t resist a little hyperbole.

Dec 2, 2010 — On Reading Brent Anthony Johnston’s “Soldier of Fortune”

I thought Glimmer Train was for speculative fiction. After subscribing to, receiving and perusing issue 77 I discovered that, at least that edition, had no speculative fiction in it at all. Too bad. I liked the format, the photos, the personal statements of the authors. However, I found myself drawn to the last story, “Soldier of Fortune,” by Bret Anthony Johnston because it was set in Corpus Christi, a later period than when I was there, but Corpus, nevertheless.

As I neared the end of the story, I had an epiphany similar to moments reading classics when suddenly I realized that little things, that incidents that happened early on in the story that were of no particular interest, were more than I thought they were. It’s not that the story developed, but that the story revealed itself to me.

In this case, the narrator mentioned that he had always lived across the street from a certain family who had a certain daughter who was of (considerable) interest to him. The family had moved away for a couple of years to Florida, at which time they had another child, this one a boy, but otherwise the narrator had known this particular girl all his life—and always been in love with her. It is not until almost the end that the narrator (and reader) realizes that the family had moved away in order for their under-age girl to have the baby and that the peculiarly distraught geometry teacher at the high school was the father. This realization comes with the protagonist’s first sexual experience, and he is never that same again.

Whether it is a story twist or a development of character, elements of the narrative are richer for this kind of revelation. When it comes late, comes unsuspected yet makes perfect sense, our enjoyment is complete.

Glimmer Train also had an interview with Johnston. He elaborates on p. 96: “I disagree most vehemently with the widespread and longstanding notion that characters are “built” from page to page to page. If that were true, it would mean the reader starts on page one of a story with a completely vapid and vacant character, a blank slate, that will be “built” up over the course of the narrative, and then finally, upon the last word we have a fully formed, deeply imagined character. At the beginning of the story was a flat slab of concrete; at the end, there’s a beautiful mansion.”

I thought to myself that stories may be built, brick by brick, and that narratives may have causal chains, sometimes many, but that characters—truly interesting characters—are gradually revealed, just like he says.

That interview also contains a funny quote: “The poet William Stafford famously said that the trick to ending writer’s block is to lower your standards.”

And another interesting quote, this one his: “Stories are—must be—smarter than the writers.”

Winter is icumen in